1988: Kuros

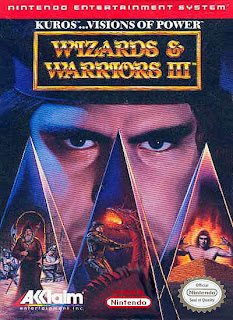

I had trouble finding a suitable title for 1988, and so this slot will go to a character who actually made his debut in the final weeks of 1987: Kuros, star of Wizards and Warriors on the NES.

Made by Rare - the company previously known as Ultimate - Wizards and Warriors takes place in a land of brave knights, kidnapped princesses and hideous monsters. Kuros must make his way through forests, caves and castles until finally facing off against a wizard named Malkil. His adventures continued in two sequels on the NES and a spin-off on the Game Boy.

Of course, Kuros is a purely generic character: even the title of his game reflects this, identifying him as merely one of an unspecified number of sword-and-sorcery stock figures. One of the few notable things about him is the strange indecision as to exactly what kind of "generic" he should be. The first game clearly depicted him as a bog-standard knight in a full suit of shining armour, while the cover instead portrayed him as a loincloth-clad Conan-alike.

This strange dichotomy carried on throughout the series until the final game, in which Kuros had the option of becoming a thief or wizard instead of a knight. Even then, the cover to the game used a shirtless, Conanish Kuros to represent the thief, who looked like Robin Hood in the game.

Kuros does have a couple of achievements to his name, though. As well as being adapted into a children's novel by Ellen Miles Wizards and Warriors was, as far as I can tell, the first British video game to make the jump to TV animation. Kuros appeared as a regular character in an obscure cartoon called The Power Team, while Malkil put in a guest appearance in an episode of Captain N: The Game Master; both series originated in the US and neither were very good. "I'd hate my arch enemy, the evil wizard Malkil, to see me like this" commented Kuros in the first episode of Power Team, and it's hard not to sympathise.

1989: Stormlord

Another sword-and-sorcery game here, but one with quite a different flavour. Conceived by Raffaele Cecco and Nicholas Jones, Stormlord was released on a number of systems in 1989. The main character is a bearded Viking fellow whose mission is to rescue kidnapped fairies while battling monsters with his deadly fireballs (or possibly gobbets of spit - the graphics are unclear).

In terms of aesthetics, what separates Stormlord from more conventional fare such as Wizards and Warriors is its weirdness. The landscape is dotted with gigantic fairies emerging from pots; instead of traditional orcs and trolls Stormlord goes up against malicious bouncing chesspieces and exsokeletal, Giger-esque creatures; and between levels there's a bonus game in which the player has to throw hearts at flying fairies, causing them to relinquish life-giving teardrops.

It would have been easy to merely crib from Dungeons and Dragons and Frank Frazetta, as many contemporary games were doing. Stormlord and its sequel Deliverance attempted a vision of a more original fantasy world, and succeeded. The low-tech graphics only add to the strangeness: it's almost as though Terry Gilliam got his hands on a heavy metal album cover.

Today, Stormlord is probably best remembered for the censorship of its Mega Drive version. Sega objected to the naked fairies, and so they were duly clad in bikinis. This misses what must surely be the more objectionable factor: bikinis or not, the giant women are used, in the most literal sense, as scenery, with the player required to physically walk over them. Anyone writing a feminist critique of video games could work a pretty good case study out of Stormlord.

1990: James Pond

The nineties saw a boom in character-based games. In Super Mario, Nintendo found a character who could represent their company in the same way that Mickey Mouse represents Disney; their rivals at Sega responded by unveiling their own mascot, Sonic the Hedgehog, in 1991. Both characters were successes, spawning toys, comics, cartoon series and other tie-is; not surprisingly various other developers jumped on the bandwagon, competing to create the next gaming superstar.

Created by Chris Sarrell, James Pond actually predates Sonic, although his series arrived in time for the early stages of the mascot craze. As you have no doubt surmised James is an aquatic secret agent; in the instruction booklet, presented as a secret dossier "for your fisheyes only", he is codenamed Double Bubble Zero and his arch enemy is revealed to be Dr. Maybe (not the Codfather? Missed a trick there...)

James Pond may not have been most original character in the world, but his game was successful enough to beget the sequels James Pond 2: Codename RoboCod and James Pond 3: Operation Starfish, along with the sport-themed spin-off The Aquatic Games. The Amiga 32CD release of RoboCod provided a cartoon intro rather reminiscent of Danger Mouse ("FI5H's top agent, James Pond, is licensed to gill!")

But despite seeming like a sure candidate for the dusty back corners of gaming history's wardrobe, James is still around. RoboCod has been re-released on various systems as late as 2009, while the series received a new entry with the 2011 mobile game James Pond in the Deathly Shallows.

1991: Lemmings

Not all the games from this period were as derivative as James Pond. In 1991 developer DMA Design (now known as Rockstar North) and publisher Psygnosis gave us something altogether more inventive: Lemmings.

Your task in the game is to take care of a horde of the titular Lemmings. These bear little resemblance to their real-life counterparts - with their blue robes and green hair they are really fantasy creatures, part rodent, part gnome or pixie, and possibly inspired by the Wombles. But as in the folklore surrounding the real animals these Lemmings are prone to walking off cliffs and dying, and this is where the player comes in. Instead of controlling the characters directly, the player must assign roles to them - bridge-builder, tunnel-digger, climber and so forth - allowing them to make a clear path to safety as they blithely carry on along their computer-guided way. As the levels become more elaborate and hazard-strewn, the process of figuring out a safe route becomes trickier.

The original Lemmings had such a perfect concept that the developers appear to have had trouble expanding on it. The first follow-ups, Xmas Lemmings and Oh No! More Lemmings, added new levels but otherwise kept the gameplay intact. After these came the proper sequels, Lemmings 2: The Tribes and All New World of Lemmings; these introduced Space Lemmings, Egyptian Lemmings and so forth but are nowhere near as well-remembered as the original. DMA ceased to develop Lemmings games after All New World, although other companies continued the series for Psygnosis.

The later Lemmings games became more and more gimmicky, with variations such as 3D Lemmings and the competitive Lemmings Paintball. There was even an attempt to create a Lemming hero, named Lomax: he starred in a 1996 platform game which moved the Lemmings to a cartoonish medieval setting. But all this seems to be missing the point of the original Lemmings. Not only was the game one of those concepts that didn't need tinkering with, the whole appeal of the characters was that they were rather nondescript and largely free of personality, but at the same time unmistakably unique.

The last Lemmings sequel was Lemmings Revolution, released back in 2000. But the original game has been frequently re-released, the most recent being a PlayStation 2 version from 2006; this version contains additions (such as the option to interact with the lemmings onscreen, using the EyeToy camera add-on) but it's still the same game at heart.

1992: Zool

Super Mario may have initiated the trend for video game mascots, but Sonic emerged as the most influential, above all establishing that iconic video game heroes must have attitude. The blue hedgehog inspired a slew of frowny-faced cartoon animals such as Mr. Nutz, Aero the Acro-Bat and Zero the Kamikaze Squirrel.

Gremlin Graphics already had a mascot in the green-skinned, pointy-eared fellow who adorned the covers of their games back in the days of Monty Mole. The title character of their 1992 game Zool appears to be a combination of three elements: the aforementioned gremlin mascot, the "with attitude" approach to character design popularised by Sonic, and the pop cultural capital of ninjas (the game was released towards the end of the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles craze).

Comic strip included in the Zool instruction booklet.

But this is not to write Zool off as a cynical cash-in. As a game character he worked perfectly: plenty of personality, and yet simple enough to make for a workable in-game sprite when scaled down. And when so many of his rivals resorted to the kind of manufactured "cool" parodied by Poochie in The Simpsons, it didn't hurt that Zool - with his bulging eyes and gangly green limbs - was maybe just a little ironic.

Zool was a successful game in its time, spawning a sequel and even the novels Cool Zool and Zool Rules. But then Zool's popularity suddenly evaporated; today, the series appears to lack even the cult following that certain other defunct series, such as Wizards and Warriors, have maintained.

Perhaps the reason that Zool failed to catch on is that, while Gremlin were on to something with the character, they failed to come up with a coherent world for him to inhabit. In the Sonic games the hero is a hedgehog who lives in the woods and the villain a mad scientist who lives in a high-tech fortress: a clear technology vs. nature theme. The Super Mario series, meanwhile, ultimately takes its cue from traditional fairy tales, with its plumber protagonist (a modern update of the Brave Little Tailor, perhaps?) rubbing shoulders with princesses, mushroom-headed gnomes and dragon-like monsters. Zool, by contrast, saw its main character make his way through a series of environments that appeared to have been literally thrown together, being constructed from household objects - a world of sweets, a world of musical instruments, a world of toys and so forth. Something just wasn't clicking.

The game didn't even have a proper villain. Sonic had Dr. Robotnik, Mario had Bowser, even Monty Mole had Arthur Scargill, but Zool had to make do with Krool - a character who was mentioned in the instruction booklet but didn't actually appear in the game. Zool 2 went some way to rectify things by adding a supporting cast: Zool now had a female counterpart, named Zooz; a pet, the two-headed Zoon; and a more tangible adversary in the cuboid, shapeshifting Mental Block, who looked rather like something out of The Trap Door.

Unfortunately, none of this was enough save the series. Although the ending screen to Zool 2 left the door open for more battles against the "all powerful" (but still decidedly camera shy) Krool, there was never a Zool 3.

The series was not entirely forgotten, however. The ending to the original Amiga version of Zool showed him kicking a small blue hedgehog out of the way as he ran home to his wife and kids; in 1995 Gremlin found themselves the target of a similarly cheeky joke. The enhanced CD re-release of Epic Megagames' Jazz Jackrabbit added a new villain, a ninja hedgehog named Zoonik...

I reacted the same way wondering why the cover showed of Kuros with only a loin-cloth when in fact the screen captures of the game shows him wearing an armor. It’s like having the touch of Robin Hood’s aura while maintaining his own identity. I enjoyed reading the whole of your thoughts on the games. I haven’t played some of the games you mentioned but I think I’ll be able to soon.

ReplyDeleteNah, although I agree that the setting of Zool wasn't very solid, with the random planets made up of common items, this isn't what killed the series.

ReplyDeleteIt was because of Commodore, it went bankrupt and the point of Zool was gone, and I am glad he stopped, because the series would then have been shamelessly a generic multi platform cash cow that would be milked dry... like that other hedgehog... Zool's awesome